For the 1980’s and early 90’s Hollywood seemed almost obsessed over making the next best action film. This is evidenced by the sheer number of action films that were released during this time, many of which would feature characters and actors that would become iconic in this crazed action cinema.

Some classics to emerge triumphant from this action film barrage to be considered are, respectively: “The Terminator”, “First Blood”, “Top Gun”, “Robocop”, “Lethal Weapon”, “Predator”, “Raiders of the Lost Ark”, and “Die Hard”. It is interesting to take notice of what these films had in common in terms of content, motifs, and messages, and how many of them, even today, are loved by so many people. It is even further astounding to observe that so many of these beloved action films came into peoples lives in such a short amount of time. With so many films having both flogged and captured the hearts and minds of so many people in such a short time frame, one must consider the potential influences these films had on society and how they helped form much of what subsequent generations now hold to be true regarding discourses of masculinity, femininity, and race.

All

of the films mentioned above have strong, extremely masculine white

males as the central character being portrayed. I say all, but with the

partial exception of one: “The Terminator”. While the story in “The

Terminator” quite often includes Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character in

full stereotypical masculine glory, the film(s) are at their core

centered on Linda Hamilton’s character, Sarah Connor, the mother of the

future “savior” of the human race, doing whatever she can to stay alive.

It is for this focus on the female heroine in the Terminator films that

I have chosen this text. Out of all the immensely popular action films

to come out of the 1980’s and early 90’s, James Cameron’s Terminator

films part one and two stick out from the salvo of other popular action

films in that they are shown depicting a heroine in mostly

non-stereotypical forms at the center of the films story, unless of

course you also consider Cameron’s other works, e.g. “Aliens” featuring

Sigourney Weaver as Ellen Ripley, and Mary Elizabeth Manstrantino’s

brilliant character Lindsey Brigman in “The Abyss”. I feel that while

the Terminator films were great pieces of revolutionary and progressive

entertainment in their own right, they were also fairly progressive and

innovative in their portrayal of femininity and masculinity in film;

however, this was not without problematical and stereotypical

representations holding these depictions back from being the truly

ground-breaking pioneers they could have been. In this essay I will

analyze the representations of femininity and masculinity, as well as

some racist issues (that nearly fell by the wayside in my pursuit of

Sarah Connor’s femininity and the Terminator’s masculinity that I

discovered during my dissection of The Terminator and Terminator 2:

Judgment Day.

I will first begin

with what I feel is the most interesting character in the series, Sarah

Connor. Sarah Connor is the mother of the future “savior” of the world,

and leader of the human resistance, John Connor. It is interesting to

watch Sarah’s progression as a character throughout these two films. We

first meet Sarah in “The Terminator” in a diner where she is a waitress.

She is clumsy, quiet, lonely, and vulnerable, but nonetheless hard

working. Throughout much of the first film, Sarah is the stereotypical

“damsel-in-distress” that we have seen in almost hundreds of films.

Sarah is much this way throughout nearly two-thirds of the film until

she is finally kidnapped by a man named Kyle Reese, who reveals himself

to be a soldier sent from the future to protect Sarah and more

specifically, her ability to reproduce and bear a child. He also reveals

to her that the child she had yet to bear would be the man to save the

world from a powerful race of machines. This knowledge that Reese

imparts wither her, sparks an interesting reaction within Sarah.

Initially becomes infused with forceful confidence and courage in

learning to defend herself in whatever ways necessary to stay alive.

Reese teaches her how to shoot a gun, use hand-to-hand combat, and even

how to make homemade bombs, all of which she is fully enthralled in the

processes of and is able to learn quickly. While this scene could be

seen as quite progressive in terms of femininity being portrayed as a

literal evolution on screen, one needs to remember that while Sarah may

indeed be learning skills that will make her strong in her defense of

herself, she still needs to be taught these skills. These skills and

“toughness” are not a natural part of her femininity.

To

emphasize this point even more so, consider the juxtaposition (even

literally, for she is standing next to him throughout the scene) of her

to Reese in this scene, who is by no coincidence, a marine. Marines have

frequently been “ideal” stereotypical representations of masculinity,

it would seem there would be no one better to teach her the ways to

being a “man” and the skills necessary pertaining to taking care of

herself. Interestingly, in this same scene, only moments later, Reese

begins crying and immediately upon seeing this, Sarah rushes to his

side, puts her arms around him in quite a motherly manner, as if caring

for a crying son, and asks him if everything is alright. They

subsequently profess their love for each other and Sarah succumbs to his

virgin (more about this later) advances, and Sarah becomes pregnant

with future leader of the human resistance.

The

very sudden and stark change in character for the both characters,

particularly in Sarah, came quite unexpectedly. It seemed that this

scene at the lonesome street side hotel came near full circle to where

it began. They arrive at the hotel with Sarah being both scared, and

vulnerable. She then learns how to protect herself and becomes almost

instantly more assertive and confident, then without missing a beat, she

instantly reverts back to her motherly role, then to a heterosexual

sexual role, and then literally to that of the role of a mother and

partner.

Soon

after this scene Reese is killed by the Terminator, which then turns to

kill Sarah. Here is where her newfound feministic, stereotype power

comes into play full force. She initially runs from the Terminator,

which technically could be viewed Sarah still as the damsel-in-distress

motif, but I contend that it is not. This time she is not just running

for her own life, but also for that of her unborn son’s, and she knows

that in order to preserve both lives she will need to end that of the

Terminator’s. She eventually coaxes the Terminator (now nothing but a

metal skeleton, more about this later also) and just as he is reaching

for Sarah’s neck to choke her, she crushes and kills him. This scene is

probably the most powerful in depicting Sarah as the feminist heroine

she is destined to become. The scene overall can be interpreted that

while the woman has the capacity to love (albeit in a heterosexual way)

and feels pain when that love is lost (Reese), she is also self-aware

enough to realize that having a strong, masculine figure nearby is not

necessary for her protection, let alone her survival, even against the

most brutal and ruthless of figures.

Her

crushing of the Terminator could very well be viewed in several

powerfully symbolic ways. The first of which could be femininities

triumph over masculinity in general. With Reese dead, Sarah needs no

assistance from any male in order to defeat the monstrous presence of

masculinity in her life, literally by crushing the very “framework”

(skeleton) in which it is presented. I also see the Terminator’s

outstretched arm, in full choking fashion to be a symbolic threat to

femininity in general. Even in “masculinity's” last dying breath at the

hands of femininity, the man is attempting to choke the life out of the

woman and whatever power she recently gained in order to defeat him. The

first film ends shortly after this scene with Sarah driving towards the

desert, now with a noticeably large pregnant abdomen. This scene

reinforces that while Sarah had fought so bravely in literally

destroying that which was oppressive to her in masculinity (albeit

stereotyped masculinity in the Terminator), it was apparent that her

central focus internally was on her role as a mother/reproductive

figure, which, non-coincidentally, is the ultimate symbol in femininity.

This only reinforces the films tendency to depict that which is natural

and inherent to women, will always be natural and inherent, no matter

what typically “masculine” skills and behaviors are acquired through a

woman’s life experience.

The

second film in the series, “Terminator 2: Judgment Day” also contains

many insightful commentaries regarding femininity, which, almost brings

itself full circle back to where Sarah began in “The Terminator”. At the

end of the first film we were left with a mental image of a powerful,

intelligent, and evolved woman. She had just defeated the Terminator (or

gender discrimination in general) by defying who she had always been

and by tapping into the inner strength she never knew she had (until she

met Kyle Reese of course). The first time we see Sarah in the second

film it is nearly 10 years later and she has been forced to stay in a

hospital for the mentally unstable. It is worthy to note here that she

is in the mental hospital because of what she had so assertively

described experiencing with the Terminator as well as what she had

learned about the future from Reese. One could also take this

symbolically in that when a woman is breaking out of her

heteronormative, stereotypic femininity, society tends to “lock them up”

and push them out of sight and out of mind, classifying them as radical

or even “crazy” for trying to break away from what the status quo,

especially if their knowledge brings a threat to the white masculine

male who, in the hospital, is represented as the balding, weak, but

intelligent Doctor in charge of Sarah’s “treatment”. We first see her

doing pull-ups, sweating, and wearing nothing but a tank top (clearly

without a bra; this could be because of dress regulations for patients

within the facility but I can also see how it could be read in open

protest to such “feminine” artifacts) and scrub pants. She is more

defined and physical looking than last time we saw Sarah, especially in

her arms which look particularly strong and defined, which,

non-coincidentally are typically markers of a stereotypically “ideal”

masculine man. She comes across as now an extremely capable woman, both

mentally and physically.

It

could be inferred that she is appropriating these actions, appearances,

and even aggression from men and using it to her own advantage, which I

believe she does. This appropriation can be illustrated by the scene

with her in the hospital and she uses the knowledge (the same knowledge

she had been institutionalized for) as well as her physicality in an

attempt to escape. But, once again, her powerful femininity only gets

her so far. As she is running down the hall to the elevator literally

runs into and subsequently falls down at the feet of the Terminator. But

this time this ideal figure of masculinity is not there to kill her, he

is there to save her. What a fascinating dialectic this is! In one case

the quintessential embodiment of masculinity is present in our feminist

heroines life to kill her, and now, that same figure is again present

in her life (one could argue that he was always present in her life,

even after the hydraulic press incident, within dreams and such), but

this time it is that same embodied masculinity she had fought so hard

against that is there to save and protect her.

As

the film progresses, Sarah gradually becomes more accepting of the

machine that had been sent to protect her. But this does not stop her

from continuing in the ways that Reese had so effectively taught her. As

a side note, in a comment from John, Sarah’s now 10 year old son, to

his friend, he mentions that part of the reason Sarah had been

institutionalized is because she had gone to Mexico (presumably that is

where she was going at the end of the first film) and used her

attractiveness and sexuality to gain knowledge about various weapons.

This is intriguing because even though she has certainly grown immensely

from the first time we saw the clumsy Sarah working in the diner, she

still acknowledges the power that she has innately as a woman. And, as

taken from what John stated, she uses it to her advantage in gaining

knowledge and power that will only push her further and further away

from those weak stereotypes she once was. But once again, it must be

remembered that everything she has become up to this point in the films

has been learned, meaning none of it was portrayed as natural or innate,

besides perhaps her ability to work hard, as well as her over arching

concern for survival-both for herself as well as her son.

Ultimately

however, the second film ends on a note that, as mentioned previous,

brings the progression of Sarah Connor’s feminism almost full circle

back to where she was when she first met Reese. In the concluding scenes

of the film Sarah and John are being relentlessly hunted down by a new

Terminator, the T-1000 (that looks nothing like the original model of

Terminator), with the original Terminator along side them primarily

protecting John. This scene comes at almost a let down to Sarah’s

character arc throughout the films story. Where she once was able to

outsmart and defeat a Terminator on her own, she now has once again

become the damsel-in-distress, requiring the “good” Terminator’s

protection in order to stay alive and protect her son. The “good”

Terminator eventually kills the “bad” Terminator and sacrifices himself

in behalf of Sarah and John that they may live on in peace. I see this

as problematic for Linda Hamilton’s portrayal of the character. Indeed,

she is still a very strong character (she at one point wields a shotgun

with only one mobile arm); she is still far from being independent.

She

still relies heavily on the protection of an immensely strong masculine

figure in order to be safe; showing that while a woman may be able to

exhibit a strong will for success and utterly survival, it will not be

enough. This reinforces this, and shows, even perhaps inadvertently,

that being a strong woman will only get you so far when the “bullets” of

life begin being fired before it will be absolutely necessary that a

white, masculine man step in and save the damsel.

On

another note, I also found the portrayal of masculinity in the films to

be worthy of mentioning in some length because of both the films

extremely stereotyped portrayals of masculinity as well as their

somewhat progressive nature regarding gender in some of the male

characters. I will begin with the most prominent masculine character in

the film series, the Terminator, played by Arnold Schwarzenegger. The

first time we see the Terminator, in both films, he is completely naked,

giving great attention to sheer over-the-top and hyper sexualized

nature of his body. The audience is immediately met with feelings of

intimidation and awe in respect to his blatant masculinity. In some

cases, these feelings were represented in characters that either laughed

(perhaps out of shock and fear) when they saw him naked or simply

stared, knowing full well that this man has power over all present. To

watch the reactions of the men versus the women when he is seen naked is

quite informative to observe. As was just stated, the men react mostly

with either humor or looks of intimidation, while the women either

appear appalled or incredibly enticed even by his mere presence. Such is

especially the case in the bar scene. The Terminator walks in naked and

demands the clothes, boots, and motorcycle of a man, of which the man

refuses. The Terminator then throws the man onto the hot stove and

demands the artifacts yet again, this time he is successful. This not

only reinforces gender stereotypes, and validates violence as being

redeemable, but also reinforces the heteronormative nature in the two

films (as a side note, In Terminator 3, the Terminator first appears in a

gay bar, of which the reactions are quite the opposite of what the bar

scene in Terminator 2 was like. With Terminator 3 being made almost 20

years after Terminator 2, could this be a commentary on the more

frequently visible departures from heteronormativity in today’s society?

An interesting thought indeed).

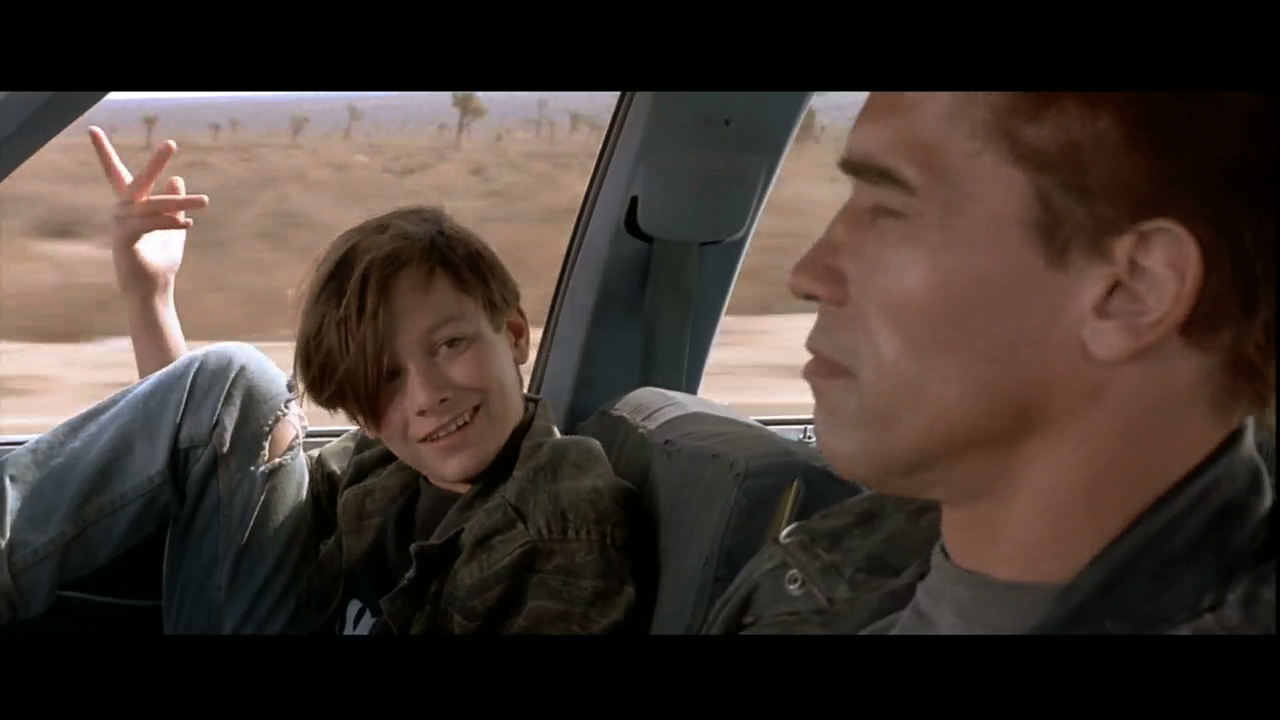

While

much of what the Terminator is in the film is extremely stereotyped

masculinity, there is, I feel, some aspects of the Terminator,

particularly in his relationship with John that I feel are progressive

and extend beyond his “machinistic” masculine stereotypes. Perhaps the

best example that would illustrate my point most fully is the scene

where John is teaching the Terminator how to play “High Five.” As quoted

from Sarah Connor’s voiceover in the scene: “Watching John with the

machine, it was suddenly so clear. The terminator wouldn't stop, it

would never leave him. It would never hurt him or shout at him or get

drunk and hit him or say it was too busy to spend time with him. And it

would die to protect him. Of all the would-be fathers that came over the

years, this thing, this machine, was the only thing that measured up.

In an insane world, it was the sanest choice.” (Terminator 2:Judgment

Day). This description of the Terminator when juxtaposed to John’s

foster father who is portrayed as lazy, and possibly even a drinker,

gives credibility to Sarah’s observation-which, coming from Sarah, is

profound in and of itself. Here is a “man”, one who had originally tried

to kill her ten years previous, suddenly becoming the primary father

figure for her ten year old son. Is this symbolically allowing brute

masculinity to be accepted, or to be overlooked? And if this model of a

man is in fact “ideal”, complete with all its capability of violence, is

also the ideal father figure to the “savior” of the human race, then

what is does that say about all the father’s who defy these stereotypes?

Kyle

Reese is one such figure in the films. Reese, although a marine and a

fighter, is ultimately a sensitive and vulnerable character. For

example, in the first film Reese explains to Sarah that he is a virgin.

When he states this to her, all of his subtly innocent characterizations

(not being familiar with certain phrases, objects, etc.) make sense,

and for a time, Sarah views him as the ideal father figure and spouse.

It is interesting to further observe how Sarah, originally loving

someone who defied the stereotypical masculinity (especially that of a

modern marine in terms of moral code) to subsequently looking to

someone, who she had originally feared because of his immense

masculinity and sheer power and control he represented, as a father

figure for her son. Whether this is a statement further backing my

thesis of these issue ultimately, coming full circle back to where these

characters and stereotypes began, despite seemingly taking “two steps

forward, one step backward”, I will not consider too strongly but feel

that the irony that is set forth in the Sarah-Reese-Terminator

“relationship” is too strong not to give adequate attention to.

This

sensitivity exhibited by Reese could also be extended towards John

Connor as well. This sensitivity seen in John, I feel is in fact

progressive in its display. John, despite initially being portrayed as

smart, rule-breaking, and disobedient thief, we observe later on that

John has the sincere capacity to love and to be sympathetic to one’s

needs, as is seen particularly in relation to his mother. Throughout the

second film, the “idealized man” in symbolic terms (as well as Sarah

Connor’s terms per mentioned previously), the Terminator, is the figure

that is constantly there, repeatedly saving and protecting Sarah (“the

woman”) and her son, John. However, we know that in the end, after the

“war” with the machines, that it will ultimately not be the insensitive

Terminator that wins, but will be the sensitive John Connor, one who

feels an honest and hopeful connection with and love for human beings.

Those qualities such as love, compassion, understanding, and sensitivity

have been traditionally attributed to be more feminine qualities, but

here they are perfectly alert in John, and it is those qualities that

will eventually save the human race, not the brutal savagery with no

regard for the human condition that the Terminator race carries with it.

This could be looked at as the ultimate triumph in femininity over

stereotypical masculinity. When looked at in a symbolic sense, the

Terminator’s as the “race” of masculinity and the human resistance as

the “race” of feminism, it makes sense.

In

conclusion, I found the Terminator films to be incredibly insightful

into how representations of masculinity and femininity are being

developed in the media and the progress that is made therein. I feel my

examinations and queer readings involving these topics of social justice

were based off keen observations of my own and did not try to analyze

the particular intent of the filmmaker, I merely made inferences

regarding these representations of femininity and masculinity. Despite

what progress was arguably made in the films with respect to these two

topics, I feel that my thesis of concerning these progressive ideals

while taking two steps forward in some instances, almost always take one

step back-reverting to age old stereotypes and representations. These

stereotypes, even in such blatant models such as what is contained in

the Terminator films, are clearly all but impossible to draw completely

away from in film for any lengthy amount of time before they draw us

back in like a magnet. Consider the films eventual conclusion: that when

all is said and done, saving motherhood and its reproductive

capabilities are central to the human existence and salvation.

In

order to protect this gift, a woman must be capable of taking care of

herself, but only to an extent. No matter how strong a woman may become,

such as Sarah Connor, she ultimately still needs a man with those

natural, innate, even hegemonic abilities that only a man can possess in

order to survive and be protected from the dangers of the world. Also,

consider that because of her role as a mother, it will never be herself

that is meant to save the world, it is her son; so she is almost

expected to behave completely altruistically in behalf of the welfare

and safety of her child. In the end I felt that both my initial

curiosity and research questions were both answered, as well as my

general thesis statement. There may be more truth then we realize with

the Terminator’s statement, “I’ll be back”, for if the seeming

progressive nature for purportedly definitive roles for both masculinity

and femininity revert back to the all too common stereotypes from which

these characters spring, the conceptualization of the “terminator” in

all it’s blatant masculine glory, will indeed “be back” again, and

again.

No comments:

Post a Comment